Housing SD

2019

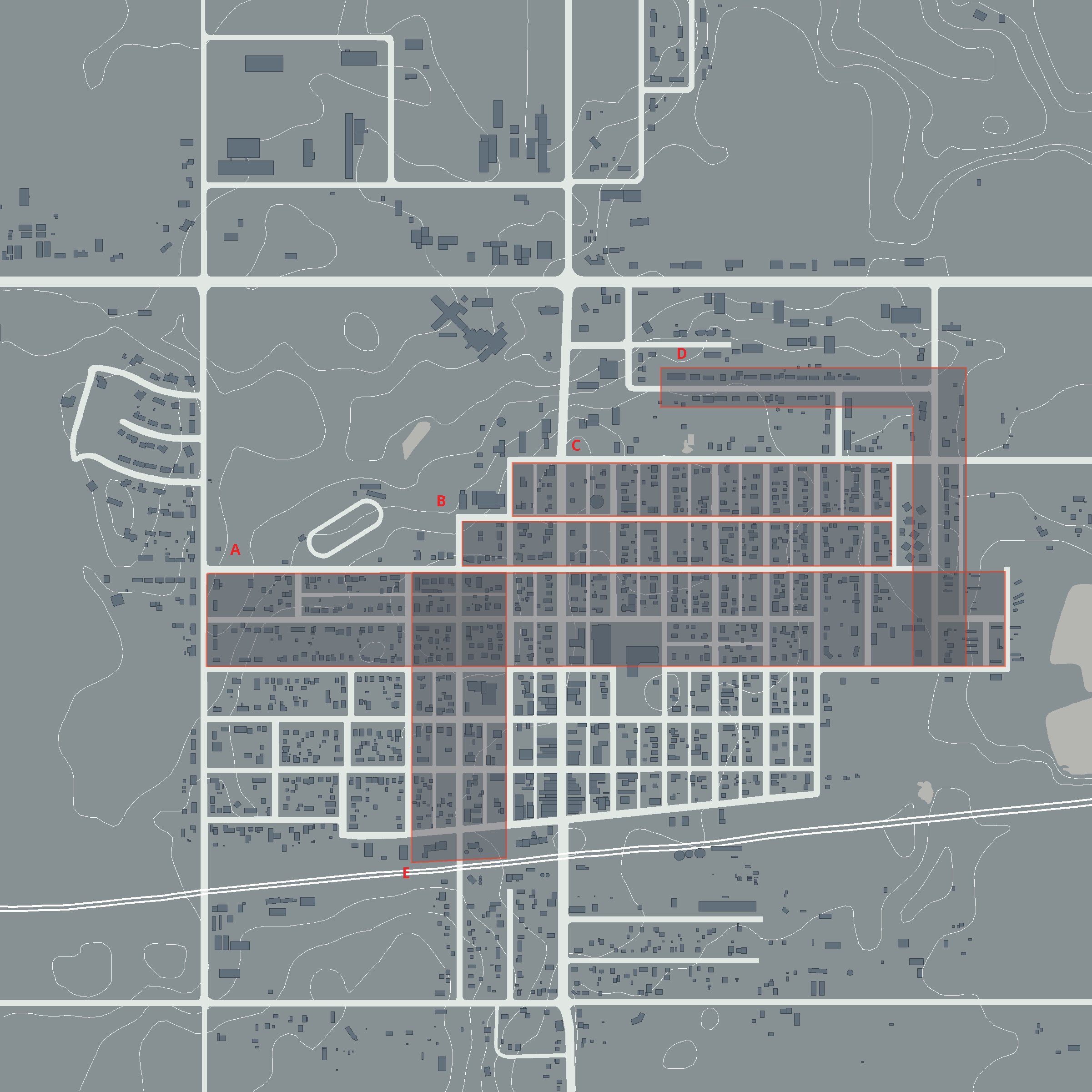

Brookings, South Dakota

Advocacy and Design for Small Cities: Webster & Wagner

A DoArch Public Works project combining service, student outreach, housing design, and political action. With research assistants Elisa Stamatakis, Jared Nurnberger, and Kristie Moss.

One of the fundamental roles for architects is advocacy. This often is the subjective and unquantifiable task of teaching design and describing benefits to communities or clients more intent on shorter term outcomes and solutions. It also involves the task of arguing for urbanism in places that have experienced both population and economic loss for over a half century. Advocacy of design for community also requires proposals for the physical and built environment, a more specific and easily criticized subset of the ephemeral, less tangible notions of community building or economic development.

Housing conditions in South Dakota differ largely from the rest of the nation for many reasons. At first glance, the state’s many small towns seem to be doing quite well, especially by comparison. Similar communities in the central or southern-plains states that would have long ago disappeared are still around. Small towns in the Dakotas, while perhaps not as visually or nostalgically kept as they might have been fifty years ago, are holding steady in terms of population, and, relative to their scale, changing and adapting to current economies and industry. Abandonment hasn’t been the issue over the last generation or two, but a shifting and aging demographic, combined with the removal of nearly all publicly funded housing, has created a crisis.

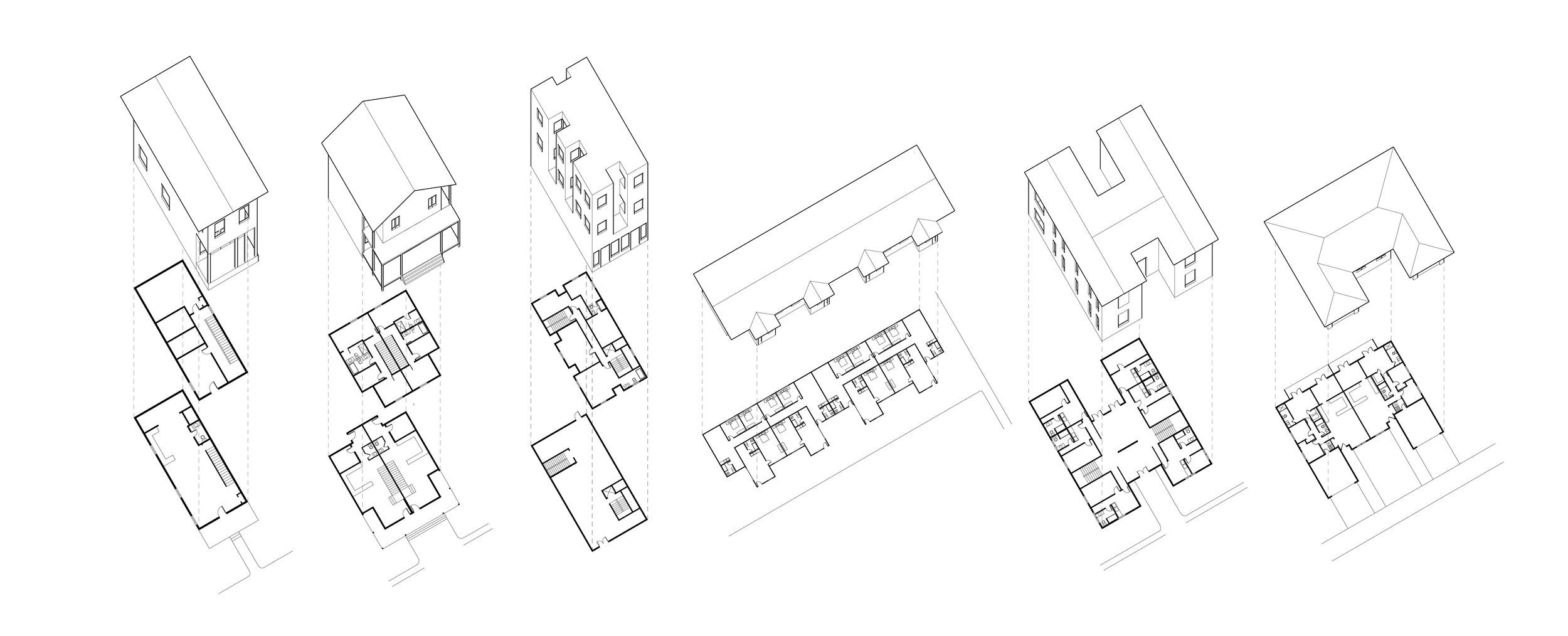

The lack of housing occurs in some towns just beneath the visible surface. These are communities like Webster, SD, where a single cultural population exists, and housing challenges revolve around the central issue of limited housing types. New housing has been almost completely limited to single family residential, and other types, such as twin-homes or senior living units, cannot be built fast enough when (and if) they are developed at all.

The same lack of housing, in other cases, is not hidden at all but in plain sight. Wagner, SD, a “bi-cultural” community located on the Yankton Sioux Tribe Reservation, is an example where cultural and economic conditions within the community have combined with the disappearance of public funding to create crisis. New housing of any kind follows established “white” residential models, lacking communal spaces from the building scale through the neighborhood scale. Even a kind of “flight” has started away from the town center toward the Fort Randall Casino and state recreation areas fifteen miles west.

SDSU DoArch has been working as an advocate for small cities and towns across South Dakota since its founding. It has connected students and required coursework in community service and design. Advocacy for planning and smart growth, preservation of Main Streets, and construction of public spaces have forged strong connections. Teaching both the potential and limits of the physical city distinguishes these efforts as active, material, and result-based. The seemingly simple act of making has produced grounded, tangible results. Promises of action based on financial, political, and/or popular consensus are simply harder to achieve, and as a teaching model, do not produce physical results or demonstrate to students potentials of excellence within the discipline.

The work was initiated with fourth year students challenged to study, analyze and propose housing solutions using Webster and Wagner as example cities. Each community had come to DoArch in different ways. Webster was visited by first year students, resulting in a large model and several documentation studies as part of a studio assignment. Webster, as much as any small city in the state, is actively and aggressively pursuing development and growth. It participated in a design:SD charette as part of its own initiative for creative ideas and reinvestment in community.

Wagner continues and expands upon its connection as an SDSU Extension Horizons community. The city has worked on “deliberative dialogue between the Native and non-Native communities with the goal of creating a more prosperous and equitable future.” The cultural divide in Wagner underscores the challenge of architects and designers working there. Advocacy for good design can easily be overshadowed by the necessity of bridging generations of discrimination, a history of inequitable housing, and practices of both physical and cultural segregation. Promises of a building, of housing development, clinics or community centers, or any public construction are weighted with expectations greater than the sum of its assembled parts. Currently, Wagner is struggling with housing is ways similar to Webster (in terms of limited typology), but more significantly as a bi-cultural community needing significant public investment. It needs new models based on the largely unacknowledged cultural requirements of the Native community.

Student research began with an investigation of housing types in Webster and Wagner. Both cities have a population under 2000, and were established in the early 1900s as agricultural towns along a railroad. Their Main Streets, once commercial and public centers, are still active but in need of continual maintenance and reinvention. Retail and public space have generally moved to the state highways (the “four-lanes”) are the new commercial centers, with industry and institutional locations built at the scale of the car.

Housing on Main Street is rare. Few, if any, of the two story buildings have occupied or residential upper floors. Rumblings by some of the younger members of the community, often called “returners,” have started to pursue the expensive renovations necessary for upstairs live/work or rental units. Vacant lots exist as potential new construction sites. Typically, however, these locations are seen as economically limited due to parking, pedestrian traffic, and construction expense. The decision to build new within only a mile or two of Main Street offers the ease of an unrestricted site and few zoning or signage restrictions. Incentives for preservation, smart growth, or reinvestment in downtowns are absent.

Other student design typologies included duplexes, townhouses, rowhouses, and other multi-family buildings. In addition, senior living, assisted living, flats, and transitional housing were identified. Examples of these exist in Webster and Wagner, but each would benefit by adding many more. They are in high demand and new housing of any type are almost immediately occupied.